After a lengthy discussion on social media yesterday, with a woman, who didn’t understand what’s wrong with a 100%-male panel on communications workshop, organised for women on International Woman’s day, I thought I’d write about the female influences in my scientific life.

My mom’s dream was to be a surgeon. Unfortunately, being born during a dictatorship and in a poor family, her chances of getting a degree were very slim. However, being the strong-willed and determined woman she is, she had her own hairdressing business by the age of 24. A business that she still owns and manages to this day. She also has many professional accreditations, and I remember the tough times when she had to work, manage her business and employees and study in the evenings, all while having a very young family.

When my dad died in 2001, my mom was suddenly left alone with an 8 and 14-year old (me), a life designed and planned for two parents, and a business to run. She overcame everything, thrived and put my brother and me through university. We were very privileged that we didn’t have to work during our studies. However, I did work with my mom during my studies, when her employee at the time left to open her own business. I became quite an expert in eyebrow waxing and nail art if I do say so myself. Since she couldn’t fulfil her dream of becoming a surgeon, she dreamt that I would (Sorry mom!). However, this meant that I grew up with the idea that I could be anything I wanted to be! Like any child should. One of my cousins became a medical doctor, while her sister became a pharmacist in big pharma companies. They are 10 years older than me, so I could, from an early age, see that women could be successful businesswomen, doctors, or anything they would like.

Me and mom, ca. 1990

Me and mom on my wedding day, in 2015

When I was born, my mom was employed as a barber and didn’t have maternity leave. This meant that she had to go back to work very soon after birth, and I was too young to be in the nursery. A friend of my dad had recently become unemployed (blame the textile crisis of the ’80s) and agreed to be a childminder until I was old enough for nursery or until she got a new job. Well, she got a new job, but I stayed there. Her mother, a 50-year-old housewife, became my childminder, and I stayed there for 16 years! However, they became more like my grandparents and their daughters, single women who lived at home, like my sisters. They definitely are to blame for my love for sewing (all seamstresses) and always told me I had to be independent and never depend on anyone. I think they were definitely too progressive for their times. My summers would be spent playing with the kids in their family, mostly girls, who still are like family to me. One of them proudly taught me how to read before I started primary school.

Did I know from an early age that I wanted to become a scientist? No. Did I make a conscious decision to become one? Also not.

Freshers’ week with a student parade

Here I am, second year of uni, wearing the traditional student gown (and a perm)

In Portugal, admission to a public university is a bit different from other European countries. You choose 6 combinations of degree/university and then compete for a place with everyone else in the country. Everyone is ranked and placed exclusively according to their grades. So you never know who you’re up against and what choice degree you are placed in. There are better chances to get a place in a private university, as these are not decided by the rankings. However, the top 10 universities, according to Times Higher Education, are public. Also, some degrees, like medicine, are taught exclusively at public universities. I ended up in Biochemistry, without really knowing what biochemistry was. My, was I in for a treat!

The faculty is an engineering and tech campus, where most of the students were men (at the time, at least). Except at the chemistry department. Contrary to most European countries, chemistry was considered to be a “girly thing”, and chemistry and biology shared a building. The teaching and research staff was pretty 50-50, which really helped us, girls, not feel like it was something we could never achieve. Actually, one of the most prominent figures at the faculty is a female physicist, national and international award-winner Prof. Elvira Fortunato, who heads the Material Science department.

To this day, I was only supervised by women, which was never a conscious choice, but rather by chance. I did my first lab internship with Dr Sofia Pauleta, and then went on to work under great women during my BSc and MSc projects: Prof. Teresa Moura, Prof. Mª da Conceição Loureiro Dias, Prof. Graça Soveral, Dr Catarina Prista and Dr Joana Matos. Their groups were also primarily composed of women.

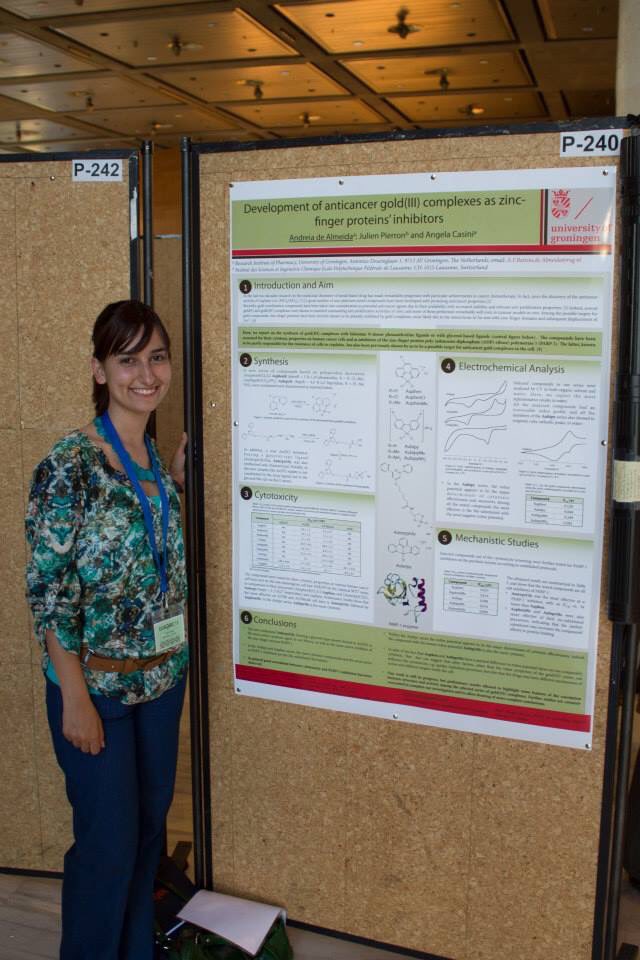

During my PhD, I again worked under the supervision of two great women: Prof. Angela Casini and Prof. Geny Groothuis. Angela was a young PI at the time, while Geny was the head of the toxicology group. This arrangement was quite unique: we were a group within a group and had the advantages of being a younger lab, with the support of an established lab. I know lots of people are scared of working for young PIs, but I can’t stress enough how great it can be! As for everything in life, you need to choose well and there are always bad apples. But a young PI will be very involved and supportive. Basically, in those early stages, your success is also their success, and they will be your biggest cheerleaders. That was certainly my case, and I can’t thank Angela enough for the help and support during my PhD and first postdoc.

Medicinal and Bioinorganic Chemistry, in Groningen, group photo in 2015

Pharmacokinetics, Toxicology and Targeting group photo just outside our building.

After my PhD viva, with my supervisors, committee and paranymphs.

Medicinal and Bioinorganic Chemistry group photo in 2016, Cardiff

Medicinal and Bioinorganic Chemistry Holiday group photo

Medicinal and Bioinorganic Chemistry group celebrating International Woman’s day in 2018

Since 2018, I’ve been working with Prof. Rachel Errington, who is also a force of nature. Rachel took on her stride the role of director of the Division of Cancer and Genetics, a few months before the pandemic hit. Honestly, I can’t imagine someone better for this role. She did her best put sensible plans into action and get us all back to work while keeping us safe. She took so much on her shoulders and, yet, she still managed to guide our group during these troubled times.

From the 12 students I’ve supervised until today, from BSc to PhD students, only two were male. This was again not by choice but perhaps aided by the fact that a female PI might attract more female students. All those students (both men and women) taught me so much and helped me become a better supervisor. Supervising students can be challenging at times, but they teach you so much.

This is already a very long text, so I’ll leave you with a photo of my (female) dog because everyone loves a good dog photo! And she is extremely photogenic.

Andreia